Infectious Diseases & Epidemiology

This research area delves into the epidemiology of various infectious diseases, emphasizing their prevalence, risk factors, and associated health outcomes. It particularly highlights the innovative use of wastewater surveillance as a potent tool for monitoring and understanding the dynamics of infectious diseases within communities. This approach allows for the timely detection of disease prevalence and the identification of emergent health threats, ultimately aiding in the formulation of effective and responsive public health strategies and interventions.

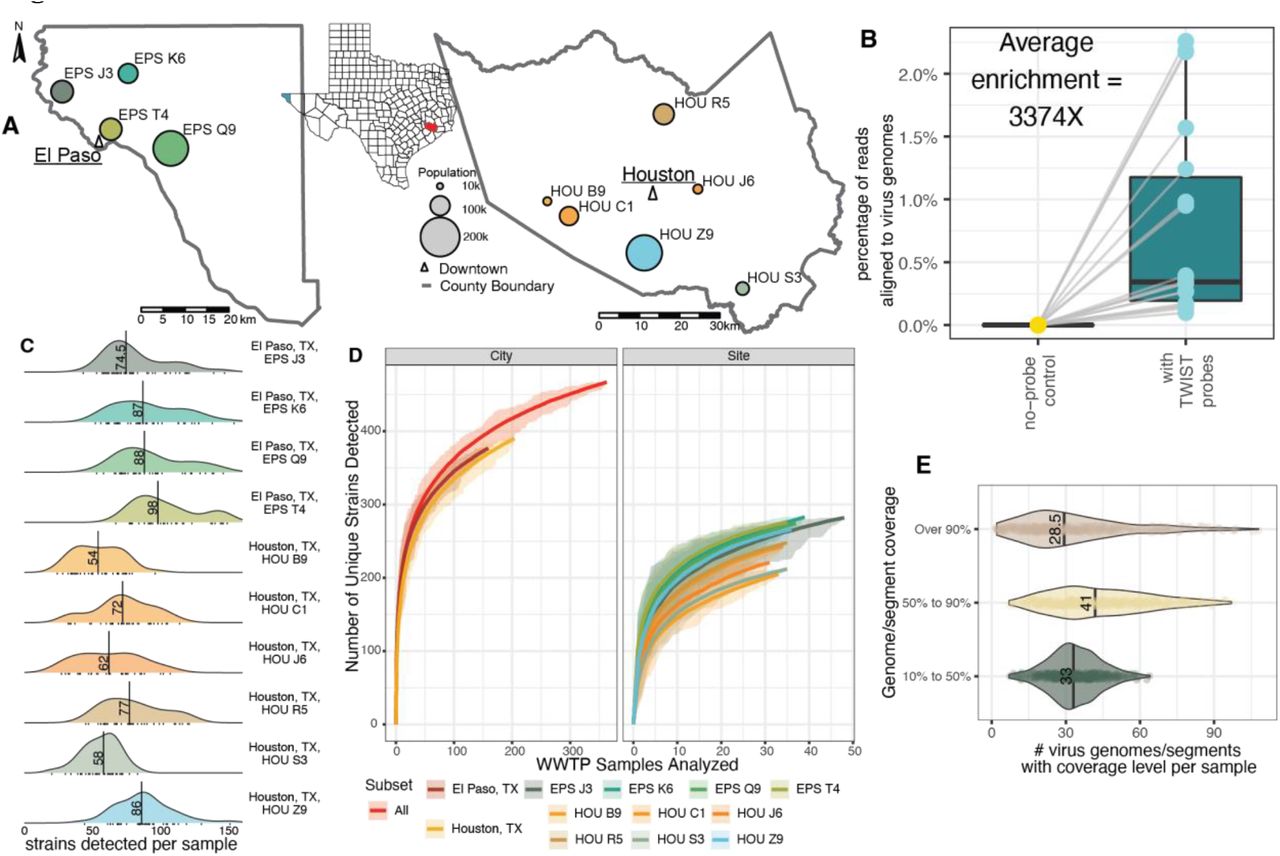

Wastewater is a discarded human by-product but analyzing it may help us understand the health of communities. Epidemiologists first analyzed wastewater to track outbreaks of poliovirus decades ago, but so-called wastewater-based epidemiology was reinvigorated to monitor SARS-CoV-2 levels. Current approaches overlook the activity of most human viruses and preclude a deeper understanding of human virome community dynamics. We conducted a comprehensive sequencing-based analysis of 363 longitudinal wastewater samples from ten distinct sites in two major cities. Over 450 distinct pathogenic viruses were detected. Sequencing reads of established pathogens and emerging viruses correlated to clinical data sets. Viral communities were tightly organized by space and time. Finally, the most abundant human viruses yielded sequence variant information consistent with regional spread and evolution. We reveal the viral landscape of human wastewater and its potential to improve our understanding of outbreaks, transmission, and its effects on overall population health.. (Check our publication: Comprehensive wastewater sequencing reveals community and variant dynamics of the collective human virome.)

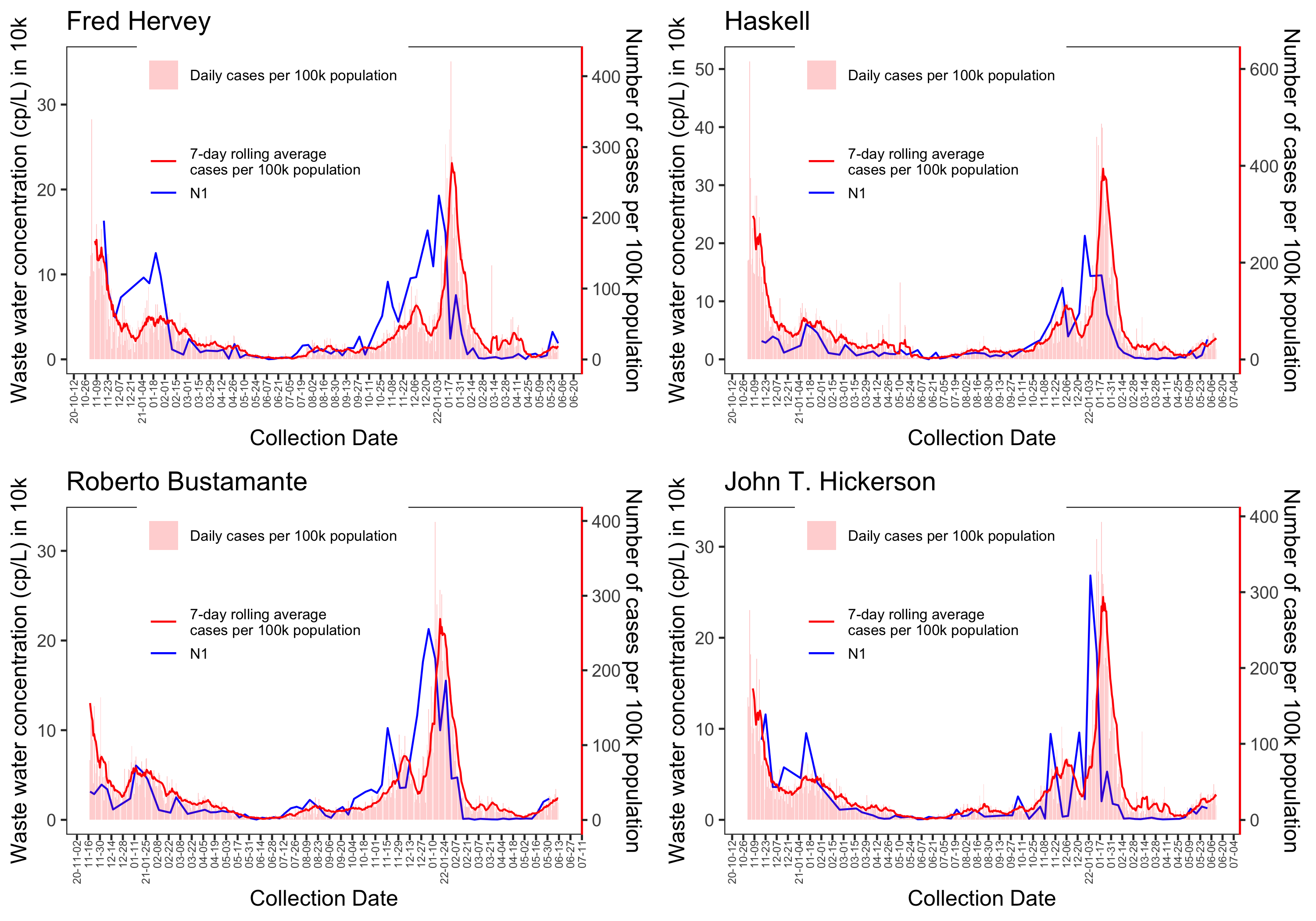

The border city of El Paso, Texas, and its water utility, El Paso Water, initiated a SARS-CoV-2 wastewater monitoring program to assess virus trends and the appropriateness of a wastewater monitoring program for the community. Nearly weekly sample collection at four wastewater treatment facilities (WWTFs), serving distinct regions of the city, was analyzed for SARS-CoV-2 genes using the CDC 2019-Novel coronavirus Real-Time RT-PCR diagnostic panel.This study is an assessment of the utility of a geographically refined SARS-CoV-2 wastewater monitoring program to supplement public health efforts that will manage the virus as it becomes endemic in El Paso. (Check our publication: Assessment of a SARS-CoV-2 wastewater monitoring program in El Paso, Texas.)

We studied the link between neurocysticercosis and conditions like epilepsy and severe chronic headaches in Burkina Faso. While previous studies identified connections between cysticercal antigens and epilepsy, the relationship with headaches was uncharted in West Africa. Using data from 60 villages, we found that those with cysticercal antigens were more likely to have both active epilepsy and severe headaches. This groundbreaking study suggests that preventing cysticercosis could help reduce these neurological conditions in the region. (Check our publication: Estimating the association between being seropositive for cysticercosis and the prevalence of epilepsy and severe chronic headaches.)

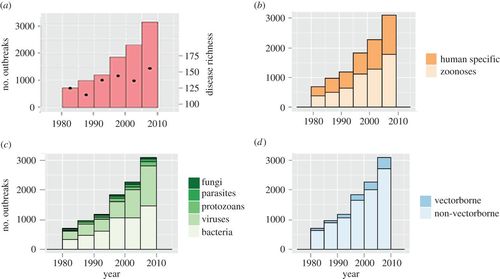

We analyzed a 33-year dataset (1980–2013) of 12,102 infectious disease outbreaks worldwide, involving over 44 million cases in 219 countries. This data, combined with the ecological characteristics of the pathogens, showed that bacteria, viruses, zoonotic diseases, and vector-transmitted diseases were the primary outbreak causes. After accounting for factors like disease surveillance and communication, we found a significant increase in the number and diversity of outbreaks since 1980. Even when considering the rise of Internet usage (from 1990) as a potential bias in reporting, the trend of increasing outbreaks persisted, though per capita cases decreased. These findings highlight the evolving nature of global disease outbreaks and the importance of surveillance. (Check our publication: Global rise in human infectious disease outbreaks.)